NOTE: This is a summary of the current amended menu selection, rationale, and other information.

The full study, including revised scientific protocol and the expanded nutritional and food selection process as approved by the University of San Francisco Medical School Committee on Human Research can be accessed at this link (pdf).

This ad-free article is made possible by the financial support of the

Center for Research on Environmental Chemicals in Humans: a 501(c)(3) non-profit.

Please consider making a tax-deductible donation for continued biomedical research.

A previously approved (UCSF-IRB/CHR) version that includes numerous footnoted references describing the scientific and health needs for the study can be found at this link.

Internal web footnotes do not work as well in this web summary version. They can be found in the full 66-page pdf.

PHASE 1: Exposure, Typical American Diet

During this three-day period, study subjects will consume a diet designed to emulate a “typical” American diet.

To create that diet, investigators will rely, in part, upon the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2016 study: Americans’ Eating Patterns and Time Spent on Food: The 2014 Eating & Health Module Data[xv]. A more recent edition will be relied upon if available.

The search will begin in the frozen foods section of a supermarket. Ultimately, the retailer may be Walmart because they are located in all American states making specific brands easily accessible to other investigators.

Our assumption for this strategy is that a branded frozen food is likely to be consistent in content, nutrition and contaminant exposure regardless of the location of purchase. This is not a certainty because processing may have taken place at different facilities depending upon distribution and location of sale. We will make an effort to determine the processing facility for all goods.

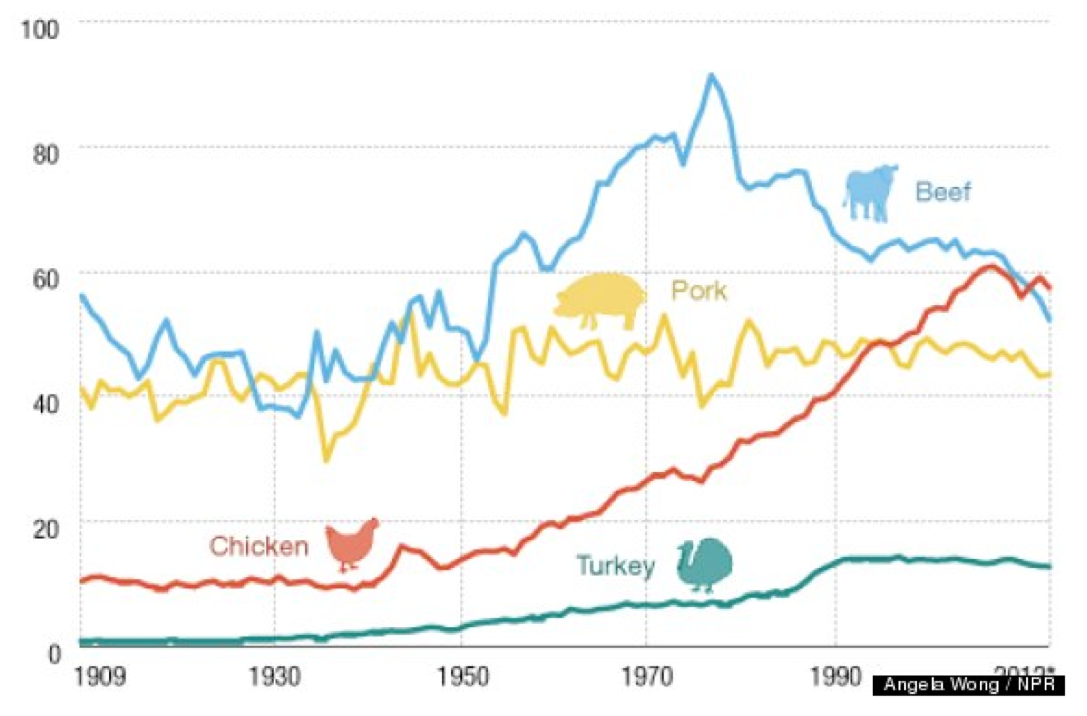

Because data from numerous sources indicate that chicken, beef and pork are the most popular meats, we will reflect this by using each for one of the evening dinner menus during the 3-day exposure phase.

Because people in all demographics increasingly choose convenient foods that save time, we will choose complete meals with an emphasis on being as nutritionally balanced as possible — meat + vegetable (preference on leafy green or cruciform) + carbohydrate (pasta, potato etc.).

In cases where a suitable complete meal is not available, we will select multiple items and combine as a meal. Items will be prepared as indicated on their labels. This will, inevitably mean microwaving frozen foods in plastic containers or in paper containers with plastic liners.

To best reflect “typical American” meal and to assure widespread availability and reproducibility, we will select best-selling brands.

PHASE 2 – Reduced contamination, commercial

Once a menu has been established for the typical exposure phase, the components of this diet phase will be structured to emulate the typical exposure phase meals as closely as possible using less-contaminated food choices.

This phase, which has been missing from all other diet intervention studies of BPA and phthalates, offers study participants a “standard dose” of BPA and phthalates. This phase is intended not only to assess the effects of a typical American diet, but also to “standardize” food-exposure levels for each participant.

Standardized food exposure levels, combined with the final phase (minimum non-food exposure – NFE) may be useful in establishing estimates of overall individual NFE.

Foods and beverages will be obtained from Organic Certified sources, selected for minimum processing and plastic food contact materials. Currently, Whole Foods is the only national chain that prohibits biosolid use in its foods and may be a primary source because its availability facilitates reproducibility by other investigators.

Other widely available sources will be sought, especially from among direct-shipping vendors who adhere to the enhanced organic rules developed by this study’s investigators.

- No plastic contact. Exceptions are not preferred, but may include BPA and phthalate-free nitrile gloves and tubing such as Tygon S3 B-44-3 Beverage Tubing or other manufacturer’s equivalent.

- Any plastic product used must be tested to assure manufacturer claims because studies have shown that some manufacturer claims are false.[xvi],[xvii],[xviii]

Preparation & cooking

The following are forbidden:

- Sous vide

- non-stick pans

- most cooking oils

- plastic utensils

- plastic prep bowls

- synthetic gloves

- plastic bags

- plastic wrap

- drip coffee makers

- Sodastream

- Keurig and other “pod” beverage makers

- Beverages in cans, plastic bottles or glass.

PHASE 3: Enhanced organic

This diet will work to provide identical menu items served in previous phases but will follow a set of guidelines developed by this study’s investigators for sourcing local food and beverage products. Those guidelines eliminate many sources of endocrine disruptors — such as recycled wastewater irrigation — that are allowable under USDA organic regulations. Adherence to these rules should facilitate reproducibility.

The guiding principals are summarized below. More details are available in Appendix 2 of this document.

- Commercially processed foods are unacceptable.

- All food will be obtained directly from local Certified USDA Organic sources whose premises have been voluntarily inspected for compliance with those and the following enhanced requirements.

- Do not consume any ingredient whose composition cannot be traced to, and inspected at its origin.

- No recycled wastewater is allowed in irrigation or other on-premises uses.

- No biosolids are allowed in irrigation or other on-premises uses.

- No food contact with plastics or recycled paper or cardboard. Minimum or incidental contact may be approved depending upon the plastic composition.

- Irrigation water must not be transported via plastic pipes. Drip irrigation is discouraged, but if used must not contact edible surfaces.

- Harvest and food transport must be in metal containers.

PHASE 4 – Enhanced, local sourced, reduced contamination diet, minimum Non-Food Exposure

The unknown — and possibly unknowable — variabilities in this class of exposures offers the greatest set of hazards to reproducibility.

Numerous non-food sources of BPA are present in the environment and likely pose significant “background” contamination which will vary depending upon the test subjects’ lifestyles and environments.

This is particularly critical because the major health effects being measured in this study; estrogen/testosterone disruptions, inflammation, and metabolic events such as insulin resistance and lipid imbalance, can also be affected by a wide variety of chemicals other than BPA and phthalates.

This is why this final phase of the protocol has been added to reduce non-food exposures of all harmful chemicals as much as possible.

In addition, the personal environments of participants (personal care products, medications, etc.) must be noted for the record and reduced in a manner that can be illuminated by comparison with measured BPA, phthalate, and microbiome levels and indicators.

The path to a revised protocol: Confounding factors lead to greater complexity and expense

This study’s investigators, from the beginning, recognized that basic nutritional levels — protein, fat, and sugar/carbohydrates would need to be the same at each level of the study. While unnecessary in previous dietary intervention studies that measured only BPA levels, the present study also measures health effects which can be affected by nutritional composition.

The widespread variance in BPA concentrations in source foods led to the realization that reproducibility of this study would require testing of all source food for BPA concentrations. Otherwise, any record of increase or decrease in subject BPA concentrations would be invalid.

That recognition led to the conclusion that a reproducible investigation required the establishment of specific baseline food concentrations — leading to accurate dose levels of BPA consumed.

Further investigation led to published papers that indicated interactions between folic acid and BPA levels[xix]. That realization made it necessary to eliminate foods which would be concerned considered methyl contributors including genistin, and soy products among others.

This was further confounded by the revelation that BPA interacts with a key blood panel indicator, Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA)[xx]. A clinical study included as part of this paper indicates that BPA may suppress serum levels of PSA in men under 65 years of age.

The potential confounding factors regarding PSA and folic acid led us to the realization that, in addition to assuring that the intervention diet nutritional content was equal in macronutrients to the baseline, we would also need nutritional analysis of micronutrients as well as every food item consumed. This compounded the complexity of the investigation as well as the costs.

Investigators’ further research indicated that the American food chain was so contaminated at every level by BPA and phthalates. The resulting food sourcing and testing demands increased the costs of the study far beyond the previous budget and would require extraordinary — and expensive — food production and processing methods to be implemented at the farm level and continuing in a highly controlled regime through processing, and preparation for table consumption.

This would require financial and personnel resources far beyond those originally anticipated.

The original study had, as its expressed outcomes to:

- Determine direct health effects: Determine if reducing BPA and phthalate levels correlated significantly with health effects that could be measured using well-accepted diagnostic blood panel elements, and

- Clinical usefulness: Offer consumers and their health professionals practical, evidence-based dietary intervention steps to improve personal health.

The ubiquitous, and inconsistent contamination of food, along with the limited availability of minimally, contaminated foods made those two goals impossible without testing every sample of food destined for the consumer’s mouth. This was obviously impractical.

This situation led us to a deeper re-examination of the handful of previous dietary interventions aimed at reducing bisphenol A concentrations in a test population. Not surprisingly, none of those previous could be replicated. Only one of those studies devoted significant attention to the reasons for non-reproducibility.

A more detailed discussion of those previous studies and this new protocol’s replication improvements is presented at the end of this document.

The evolution of this new protocol

Taking into account the results of previous published studies that indicated the ubiquitous presence of BPA and/or phthalates in every type of readily available food, the investigators sought to identify contamination sources, categorize them by food type and develop a simple, cost-effective method for selecting minimally contaminated foods.

The limited number of foods available for the intervention and variability of contamination meant that the granularity of measuring health effects by the stepwise reduction of seven different categories of food and beverages would yield little in useful data.

The original protocol offered a finer “granularity” of data because it called for nine test phases, each one week long which involved the step-wise elimination of seven contaminated product categories.

The theory was that, if BPA levels in test subjects dropped after eliminating a category, then that category was probably the cause of a certain level of contamination as indicated by blood and serum levels.

Cost constraints — primarily associated with testing costs — make the original protocol’s granularity goal impractical. For that reason, we propose four phases of three days each.

In addition, using week-long intervention periods for each category required extensive, and expensive meal preparation expense, increased risk of inadvertent contamination from non-food sources and — most likely — decreased compliance by test subjects.

The numerous additional phases and longer duration in the original protocol would not only increase the cost of testing, but would also increase food expense, impose unacceptable demands on test subjects, and place additional efforts on the reduction of non-food exposure sources.

Reproducibility depends on the availability of the exact same foods, prepared the exact same way

Creating a practical, useful study which could be economically replicated must focus on foods which are widely available nationwide. As much as the investigators would like to conduct the study with the minimum-possible contamination, the “enhanced organic” sourcing would make it both expensive and impossible to replicate.

This is because replication requires total data transparency and that requires (among other things) the ability to source materials used in the original study.

Previous dietary studies of BPA and related endocrine disruptors have not made that information available.

Those studies have given instructions to food preparers to use only “fresh” ingredients and to avoid any plastic contact. However, specific food sources and the details of their production are not available. Neither are specific cooking protocols or the identities of the utensils, pots, pans, cleaning regimen (surfactants an issue), recipes, ingredients (processing & methyl contributors an issue).

In addition, no details are available on non-food-contamination variables, environmental conditions or precautions regarding the avoidance of those.

Data regarding those conditions cannot account for the wide variability of contamination in the growing, processing, and sourcing stages. As a result, instructions in previous dietary studies account only for contamination transfer from food packaging materials and preparation.

No studies have been found that parse the growing, production, and processing contamination from that of food contact materials and preparation.

This study cannot afford to measure all of those disparate contributions directly, but will attempt to control for that lack of information and facilitate replication using the guiding principles for enhanced organic, previously described above.

Obtaining food only from sources with nationwide availability and will make that full data available.

Treat the kitchen as a laboratory and pots, pans & utensils as lab equipment.

Along with enabling replication by controlling for the systematic contamination of the food supply, we will present detailed methods and procedures, preparation, apparatus standardization, cleaning and maintenance.

All of those previous details have been omitted from all previous studies.

The precise manufacturer, model, and size of pots, pans, dishes should be disclosed as well as food preparation utensils, and appliances. The source vendor should be noted.

To minimize incidental contamination, pots, pans, and their handles should be glass and/or stainless steel and un-coated (no Teflon or other non-stick treatments).

Cooking, serving and eating utensils should be stainless steel. Wooden utensils may be used for scraping if needed.

Glass must be used for all serving items including plates, bowls, cups, and drinking glasses. This practice avoids the possibility of incidental contamination from unknown substances leaching from glazes.

Effort must be made to assure that the lowest-priced suitable items are used and that exact duplicates are widely and easily available to encourage replication.

Automatic dishwashers may be used. Appropriate residue-free cleaning agents such as one of the Extran products from Millipore/Sigma, or those from Alconox may be used.

Several cycles using the detergent should be run to remove any residues present from commercial household products. The number of those cycles should be noted along with whether the input water to the dishwasher is filtered and whether it is fed by plastic pipes. The type of plastic should be noted.

Carbon filtered water is desirable, but the volume required is impractical and too expensive for most research efforts.

Cleaned items must be followed by a rinse in properly carbon-filtered water to remove any remaining residues including those left by the unfiltered water utilized by the home dishwasher. No plastic sponges or polymer-based towels or cloths may be used.

After rinse, items should be air-dried on a stainless steel rack.

They should not be dried with a towel. Synthetic fabrics and even those from natural fibers are frequently contaminated during manufacturing.[xxxvi]

Additional contamination can come from chemicals used in laundry detergents, softeners and dryer sheets that contain phthalates used as carriers for fragrances.

In addition, home dryer drums may be coated with stubborn layers of contaminants from drying fabric contaminated by detergents and from transfer from designs imprinted on tee-shirts and other clothing. Most inks used to print the designs on fabric are phthalate-based.

Recipes are laboratory procedures

Cooking is a chemistry procedure which must be described — and adhered to — by cook/chemists.

Ingredients are reagents and must be obtained from specified, trusted sources, measured precisely, and added at the proper time at the proper concentrations.

Recipes are experimental procedures that must be measured and timed precisely.

All of those details are analogous to laboratory data provided by in non-dietary studies which provide the specific names of reagents and apparatus along with formulae and other information necessary for experiment replication.

All of those details will available with other study data and supplemental material.

And while expense prevents this study from testing the precise contamination concentrations or measure nutritional profiles, the use of the same materials from the same sources offers an opportunity to increase the likelihood of successful replication.